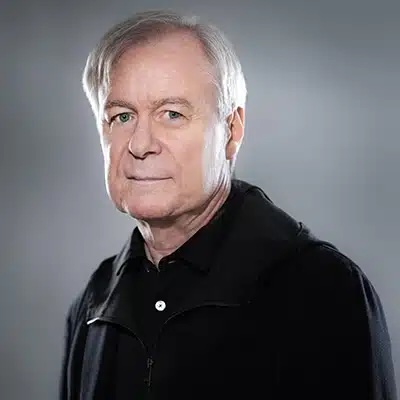

Robertson leads Utah Symphony in a varied program from sax to Rachmaninoff

David Robertson returned to Abravanel Hall this weekend to conduct the Utah Symphony in music of Pierre BoulezandSergei Rachmaninoff. Also joining the program was saxophonist Timothy McAllister in Steven Mackey’s Anemology.

Opening the program was Boulez’s Mémoriale, a short piece composed to commemorate the passing of his colleague and flutist Lawrence Beauregard. Scored for a small ensemble of six string players, two horns, and solo flute, Mémoriale is notable for the unique tone created by the instruments. The string instruments are muted and the horns are charged to stop their sound as much as possible, creating a distinctive sonic environment to showcase the flute.

Principal flutist Mercedes Smith’s melodies fluttered above the orchestra, landing briefly in unison with harmonies before shifting back out of synchronicity. Tremolos in the strings added tonal depth by contrasting with tremolos from the flute. Oscillating tempos throughout the work felt like waves bringing new textures and aural colors.

Mackey’s Anemology had its world premiere just last week in Monterey. CA (The piece is a co-commission between the Utah Symphony, Monterey Symphony, and Seattle Symphony.) In a quest to explore the air movement that creates music, Anemology pushes the boundaries of sounds normally associated with the saxophone. McAllister’s technique incorporated sustained melodic lines, multiphonic growling, staccato notes punctuated by a percussive way of hitting the keys, and even moments of just blowing air into the instrument before a pitch would ultimately emerge.

The first movement, “Spindrift,” was a syncopated blur of frenetic energy, with atonal saxophone melodies carried into pizzicato string parts before being echoed by bells, harmonicas, whistles, and bongos in the percussion section. In the second movement, “Soughing,” McAllister switched from alto to soprano saxophone which added a bright, clear tone to open choral-style harmonies in the orchestra. The depth and grace of the second movement was a needed contrast to the bombastic third movement which repeated the syncopation of the first.

Many moments in the first and third movements felt unnecessarily frantic, and some rhythms never felt like they settled into a comfortable pattern.

Still, the introduction of so many different saxophone sounds was an intriguing way for McAllister to adapt his musical color and character, and he excelled at making the unusual techniques beautiful and expressive. The second movement was majestic, and swept through the concert hall with an explorative lightness. The grounded stateliness of the orchestral sound was a beautiful counterpoint to McAllister as he soared through Mackey’s long, evocative melodies.

Rachmaninoff’s Symphony No. 1 was played after intermission. A disastrous premiere in 1897 led Rachmaninoff to abandon the work, and it was thought to be lost forever until a reconstruction from the orchestra parts after Rachmaninoff’s death. This was the Utah Symphony first performance of the composer’s First Symphony.

After the ethereal and muted tone of Berlioz and the substantial scale of Mackey, it was refreshing to explore the full dynamic range of the orchestra in Rachmaninoff’s haunted work. The symphony is powerful and filled with tension throughout. Robertson adopted a brisk pace in the first and second movements, although they still felt a bit weighed down with dramatic expression.

The orchestra was rich and robust in the first movement, and the lyrical phrasing in the woodwinds was accented by heavy, percussive phrases in the strings and brass. Robertson seemed to emphasize the dissonances in the movement, which slowed down some of the orchestral momentum.

The second movement was a textural shift with muted strings and an animated tempo. Robertson’s conducting encouraged the connection of the music as fragments of the melody moved through the orchestra, and they responded with brightness that added life to the movement. The third movement was burdened by similarities to the first, with an abundance of vibrato from the strings and overbalance from the brass which added unnecessary friction to the orchestral tone.

The fourth and final movement was the most striking. With a regal brass fanfare opening it galloped forward with lively tempos and vigor. Robertson’s conducting was focused and evocative, and the musicians responded with fiery energy.