Ballet West to open season with bounteous Balanchine

In its brief two decades, the Ballets Russes attracted a roster of collaborators that reads like a who’s who of arts history: Pablo Picasso, Henri Matisse, Igor Stravinsky, Michel Fokine, Vaslav Nijinsky, Bronislava Nijinska, and Coco Chanel, to name a few. This multidisciplinary dance company radically changed the performing arts, inspired fashion trends, and even caused a riot.

In 2009, Ballet West presented “Treasures of Ballets Russes,” and in 2016, the company created a program inspired by Nijinsky. Next week, Ballet West presents an homage to another artist affiliated with this ground-breaking company: George Balanchine.

“I come from a family of historians and academics,” explained Adam Sklute, director of Ballet West. His step-mother, Carol Christ, is the Chancellor of University of California, Berkeley, and throughout his dance career, Sklute performed in seminal Ballets Russes reconstructions, such as Joffrey Ballet’s Sacre du Printemps in the 1980s. The celebrated premiere inspired a riot among audience members in 1913.

This weekend Ballet West will be the first company in the United States to perform Le Chant du Rossignol, created for the Ballets Russes in 1925. The program also includes Apollo and Prodigal Son, created by Balanchine in 1928 and 1929 respectively. The chance to see these three ballets next to one another is like watching pages of history come alive.

“As a company, Serge Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes was a turning point in dance history,” explains Sklute. “His company introduced the one-act ballet, making it possible to see three different creations in one evening. His company made composers and visual artists as important as the choreographers.”

The vitality of these collaborations is especially apparent in Le Chant, which brings together Balanchine’s choreography, music by Stravinsky, and set and costume designs by Matisse. Watching a rehearsal of the piece, one was impressed by the athleticism and acrobatics of the choreography, including cartwheels and handstands. Balanchine created the steps when he was 21 years old and performed in its premiere as the mechanical nightingale.

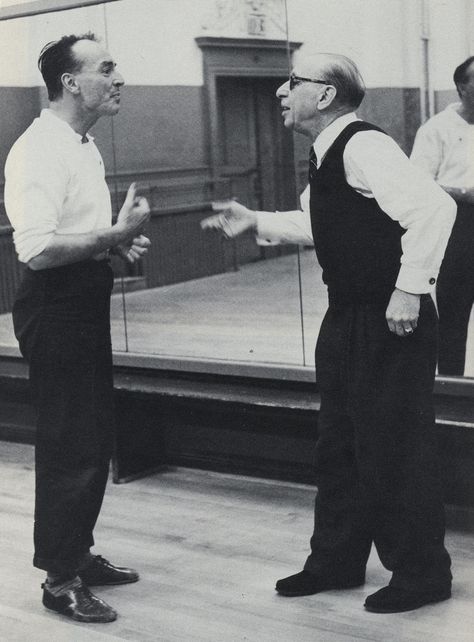

Ballet West’s reconstruction has been guided by Millicent Hodson, a choreographer and dance historian, and her husband Kenneth Archer, an art historian. In another Berkeley connection: Hodson was a doctoral candidate at U.C. Berkeley when she began collecting material to reconstruct Sacre as part of her dissertation project. Since then, Hodson and Archer have become known for their research into “lost” ballets. They worked with Sklute when he was a dancer in Joffrey Ballet and performed their reconstruction of Sacre du Printemps and Balanchine’s lost 1932 Cotillon.

Their research process has been compared to detective work because they are relying on shards of memory, drawings, reviews, and accounts of dancers who were in their late teens and 20s when the ballet had its premiere. Alicia Markova starred in the 1925 version of Le Chant as the nightingale: she was 14 years old.

Le Chant, a ballet made close to a hundred years ago, presents the story of a Hans Christian Andersen fairy-tale that drew inspiration from Ancient China. The performance has been created by a Russian choreographer, a Russian composer, and a French artist. Inevitably, this invites questions about the possibility of offensive ethnic representations. Sklute acknowledges that careful modifications were done that did not change the integrity of the choreography, but that made sure characters were presented respectfully.

For instance, the dancers’ make-up will suggest that they are wearing masks instead of pretending to be of Chinese ethnicity, something that was part of the 1925 production.

Sklute is savvy about the ways that caricatures may not have offended European audiences in the 1920s, but can be highly problematic today. He says a goal of presenting Le Chant has been to share this ballet and “to discuss and to address the way we handle representations today.” Sklute adds, “We can’t not do these works.”

Together the three ballets on view offer an opportunity to time-travel through Balanchine’s early years as a choreographer. He fled from the Soviet Union to Paris in 1924. These three works reveal seeds of his later, neoclassical style, which he nurtured for 35 years as artistic director of New York City Ballet.

In the original cast of Le Chant, Felia Doubrovska performed the role of Death. Hodson and Archer were able to find documentation of Balanchine’s rehearsals with Doubrovska in the notebooks of Diaghilev’s regisseur and Sergei Grigoriev, kept in the Dance Collection at Lincoln Center. Hodson and Archer recount that “Doubrovska once mentioned in conversation, years before our reconstruction, that her part in Le Chant was a precursor to the Siren in Prodigal Son, which Balanchine created for her in 1929. Death’s stalking, predatory moves and her ambiguous sexuality belong to the archetypal femme fatale.”

Both Sklute and Ballet West share special connections to Balanchine: Sklute began his training in Berkeley with Sally Streets, who had been a soloist under Balanchine. In the early years of Ballet West, under Willam Christensen’s direction in the 1960s, dancers performed works by Balanchine, including Serenade, Concerto Barocco, and Symphony in C.

Watching today’s company perform these ballets from the 1920s adds to the richness of their repertory. “Smart artists absorb all aspects of the arts,” says Sklute. “And so do audiences.” Indeed, this historic program is an illuminating complement to the newer works performed annually by the company.

Ballet West presents “Balanchine’s Ballets Russes” from October 25 to November 2. balletwest.org